Questioning Efficiency

Electricity Markets and Efficiency

In my recent post, Efficiency in Capacity Markets, I described how PJM was moving away from capacity payments for efficiency. The Independent Market Monitor doesn’t like these payments. Also, the Markets and Reliability Committee voted to eliminate EE (Energy Efficiency) from the capacity markets.

It may come as a shock to people that anyone could vote against efficiency. What could be better than investing in efficiency? Isn’t efficiency always a wholly good thing?

Maybe it is. Still, capacity payments for efficiency are hard to understand. I am painfully aware that I have not defined what types of efficiency can generate capacity payments.

One of the big problems is measuring efficiency. If a grid operator pays for Demand Response, the operator can measure the drop when Demand Response kicks in. Efficiency is different. Efficiency is supposed to be “on” most of the time, so measuring “what would have happened if we didn’t have this efficiency program” is much more difficult. I am going to look at efficiency programs in another post.

Efficiency for whom?

At a deep level, the question becomes “who benefits from efficiency?” For example, here in Vermont, I took advantage of Efficiency Vermont’s state-sponsored help to reduce the costs of insulating my home. Of course, my next-door neighbor didn’t benefit from this work on my house. You might claim that since efficiency is wholly good (and maybe even “holy”), his tax dollars contributed to a good cause. I have not asked him how he feels about it.

Many Vermonters are not happy with Efficiency Vermont. It has a generous budget, yet it can’t serve everyone who wants their services. The agency has a budget of about $50 million/year, or about $80 per Vermonter.

In 2016 I wrote a blog post about a comparison between paying for efficiency and paying for a nuclear plant, Clean Air versus Efficiency Charges. Clean Air Wins. A nuclear plant provides power while keeping the air clean. Everyone in the state benefits from the nuclear plant. In contrast, efficiency improvements are specific to people and groups This situation has not changed since I wrote the post in 2016.

Efficiency from whom?

As we can see from the debate in PJM, capacity payments for efficiency can be a source of contention. How do you even measure efficiency? This is a big subject, but I will give a simple example.

A Labor Day story about efficiency.

The ISO-NE program, Pay for Performance, attempts to arrange incentives for plants to come online when the grid is stressed. Pay for Performance works through the capacity market: if a plant has received capacity payments but doesn’t come online when the grid is stressed, it must give some of its capacity payments to plants that did come online. In other words, “If you don’t show up, we fine you. And we give the money in your fine to plants that DID show up.”

Efficiency resources get capacity payments, so they are enrolled in this program.

On Labor Day September 3, 2018, ISO-NE had underestimated how hot and humid it would be. Also, some natural gas plants went offline. The grid was stressed. Pay for Performance was triggered. Pay for Performance was effective in keeping the lights on.

After the crisis was over, ISO-NE and the power plants had to figure out the money transfers from non-performing plants to performing plants. This is where things went a little haywire. You see, efficiency providers only need to provide efficiency during the work week. FERC has ruled that efficiency resources are not obligated to provide efficiency during weekends and holidays. September 3, 2018, was Monday of Labor Day Weekend. Therefore, efficiency providers did not have to be available, and they were not eligible to get paid.

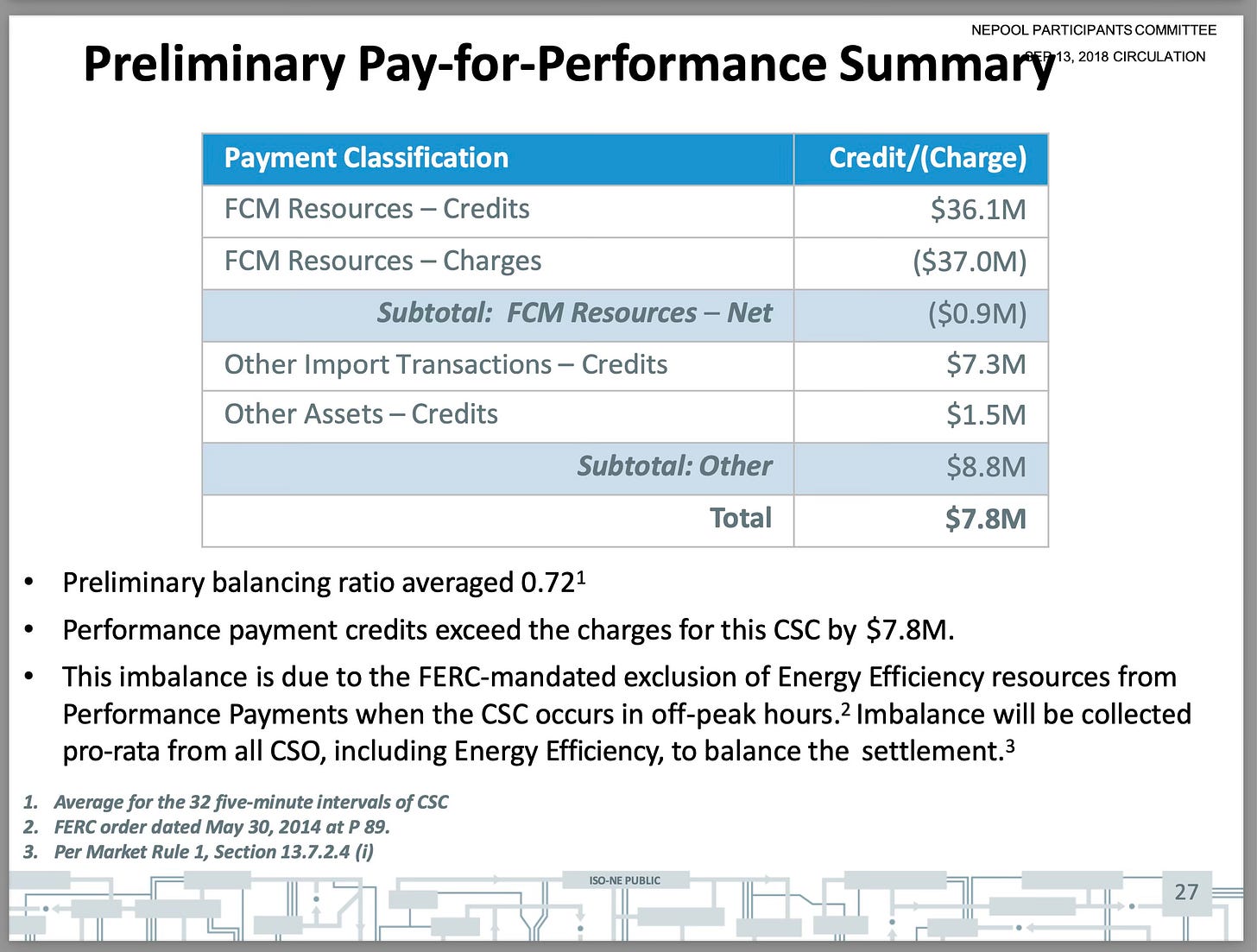

ISO-NE did a slide deck on the Labor Day incident, September 03 OP-4 Event and Capacity Scarcity Condition. I found slide 27 very amusing. (The slide is shown below.) During the incident, performance credits (money owed to performing plants) exceeded performance charges (money to be collected from non-performing plants) by $7.8 million.

This led to a question.

Where do we get the eight million dollars?

Answer:

From everyone.

The extra charges will be collected from all plants that have capacity obligations. A major reason for the payment imbalance was that FERC excludes Energy Efficiency resources from Performance Payments when the imbalance occurs during non-peak hours, such Labor Day weekend. However, the $7.8 million was collected on a pro-rata basis, from all groups that have capacity supply obligations. This means that performing plants, non-performing plants, and excluded entities (such as Energy Efficiency on the weekends) were assessed to supply part of the missing money.

As soon as you begin playing with capacity obligations, it always gets complicated. This is not because the idea of capacity is so difficult or convoluted. It’s because the various actors work hard to set the rules in their favor.

Actual Efficiency

Finally, some good news! No, the news is not that efficiency is always a good investment. The good news is that the Department of Energy finally did something right about efficiency.

This is also the only section of my post which is really about efficiency. Most of this post has been about capacity payments. It will take another post to define what efficiency sources qualify for those payments.

Let’s look at Distribution Transformers. You can see them everywhere. They are mostly little cans on utility poles. They are also mostly old. Many need to be replaced. Also, since we are trying to “electrify everything, we will require more infrastructure. In short, we need many new distribution transformers. The backlog for ordering them is about eighteen months.

Some transformers waste less electricity as heat: they are truly more efficient at “stepping down” voltage than other transformers are. Most steel is granular, but it is possible to make amorphous steel. If you use an amorphous steel core, the distribution transformer will be more efficient.

I bet you can guess what happened next. The Department of Energy proposed a rule that new distribution transformers must use amorphous steel.

However, few places can make amorphous steel. If the new rule went into effect, the backlog for obtaining a new distribution transformer would stretch toward geological time scales. (The more traditional way to express this is “the proposed rule would lead to supply chain disruptions.”)

Some Good News. The government came to its senses. Utilities only need to replace some of their distribution transformers with transformers that use amorphous steel. The title and subtitle of this April Utility Dive article by Robert Walton described the change:

DOE final distribution transformer rule adds 2 years for compliance

The agency sought a middle ground with its final rule, extending compliance timelines and adjusting efficiency targets to require less amorphous electrical steel

To quote Energy Secretary Grantholm in the article: “Our analysis shows the final standard can be met with roughly 75% of steel in distribution transformers remaining in GOES.” (GOES steel, Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel, is the kind that is mostly used in transformers.)

I hope there will be more such reasonable reassessments in the future.

Engineering Decisions

Although many discussions about energy have an almost religious tone, most decisions about energy are made based on engineering tradeoffs. In engineering, everything is a compromise. A design engineer must consider cost, efficiency, availability, reliability, impact on the environment, corrosion resistance…the list goes on.

I am happy to see efficiency taking its rightful place in this list. Not the top spot, and not the bottom either. Its rightful place, somewhere in the middle.

Efficiency is a intensely abused word. Here, it both refers to market/economic efficiency and engineering efficiency. Most activists who use the word don't really understand what it means, and it gets banded about by non technical activists as some kind of magical panacea. The worst is Amory Lovins and his 'negawatts' wordplay. As you say, correctly at the end, engineering is all about decisions/trade-offs and optimization. Energy efficiency CAN matter, but lots of other things matter too, as you have shown.

Who is the largest benefactor of efficiency improvements? The homeowner? The utility? The ISO? The homeowner’s share is likely to be quite small when compared to the others. Like you, I have taken advantage of government handouts to improve the energy efficiency of my home (new windows), and saw marginal differences in heating and cooling bills. But not long after such improvements were made, rates increased. So, any financial gain I made from improving efficiency was lost when the utility increased its rates. I have wondered if the rate increase occurred because the utility was no longer reaching is profit goals due to the diminished demand. When such things happen, as they are bound to, where is the incentive to the homeowner to improve?

Utilities tell us that by improving efficiency, they can future improvements. Because those improvements will occur at a higher price, has there been any benefit to the efficiency improvement?

This leads me to my second question. Why can’t some of the “handouts” the government gives to incentivize new generation (of unreliable value, but that is for a different blog) be instead given to utilities to incentivize them to trade out old transformers as well as bury residential transmission that is currently overhead, or to equipment manufacturers to add new capacity and shorten delivery times? It seems to me (granted, my purview is small) that our money would far better invested if we prepared for climate change, rather than try to fight it. That is, again in my opinion, a losing battle from the get-go.

I’ve long believed that subsidies should be grounded in energy density and capacity factor, and that the government should not pick winners or losers, but merely referee. But I have yet to develop a meaningful calculus to bring this idea to fruition.

Please keep up your good work. It takes time and effort to prepare these blogs, and I for one appreciate that effort. Thank you.