“Merit order” is the general rule for power plant dispatch in an RTO. In many situations, including this one, “merit” is ultimately about money.

The Balancing Authority for a grid looks at the demand on the grid, and then the BA dispatches power resources to meet that demand. Most BAs look at the demand in five-minute intervals.

All other things being equal, the BA dispatches plants in merit order. The least expensive plants are dispatched first. If they don’t meet the demand, the BA dispatches more expensive plants until the demand is met. The most expensive plant that is needed sets the “clearing price.” All the operating plants receive that price, for that five-minute interval.

This page from ISO-NE explains Merit Order.

All other things being equal, this is the way plants are dispatched. But “all other things” are not always equal. Sometimes gas-fired plants can’t get natural gas, and sometimes there isn’t water in the pond behind the hydro plant, and sometimes a plant can’t get online because the transmission lines are already at full capacity. Therefore, resources are sometimes dispatched “out of merit order.”

However, barring these issues, Merit Order is the Order of the Day.

Oil and Merit

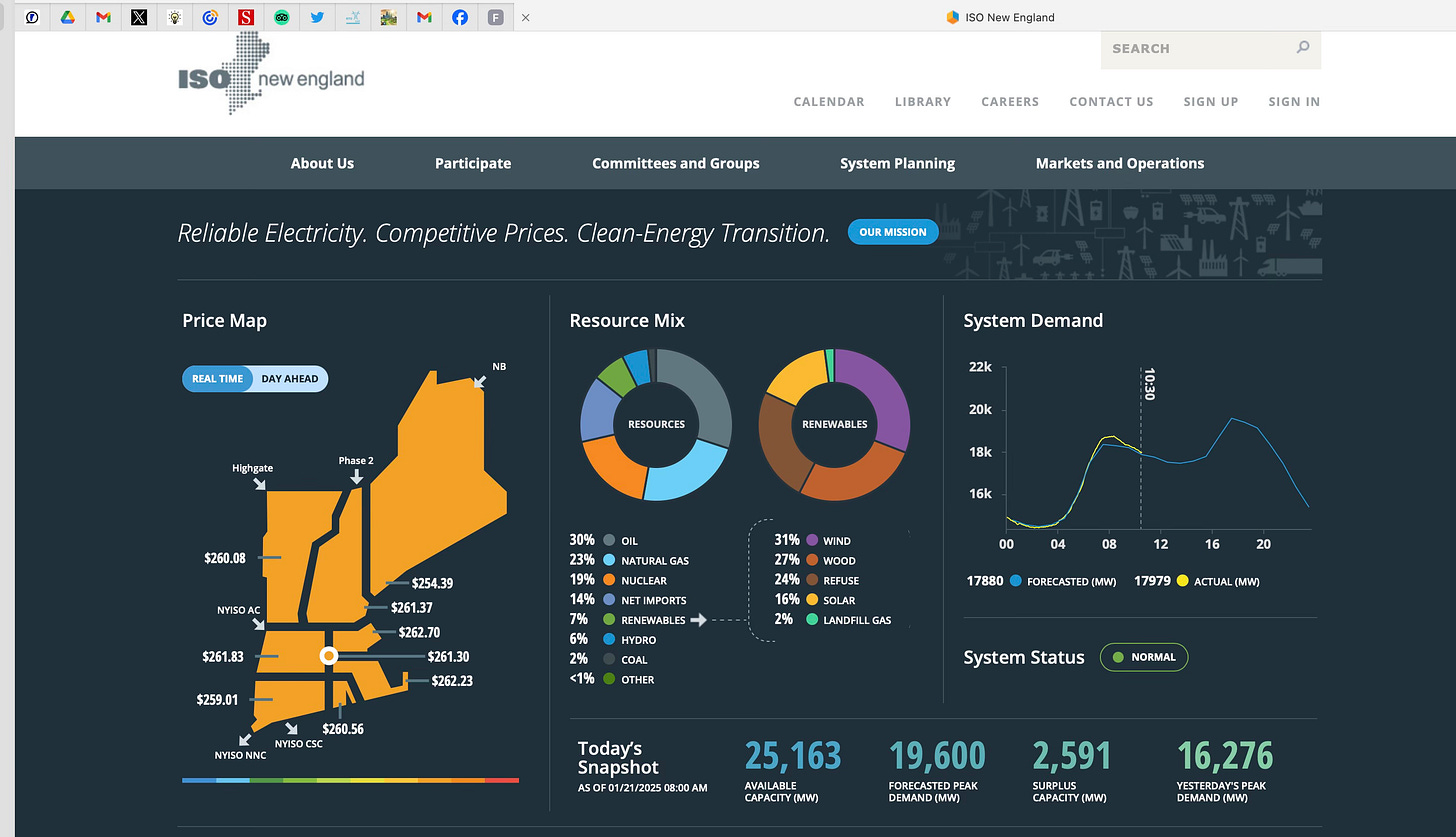

In New England, we have just recently come out of a cold snap. While the temperatures were low (near or below zero), oil supplied up to 30% of the power on the ISO-NE grid. This post will describe that recent pinch point on the grid. The screenshot below is from January 21 :

(Happily, the weather has warmed up. Oil is not a significant fuel on the grid right now. At this writing, electricity prices are around $130 per MWh instead of $260. You can follow ISO-NE in real-time here.)

During cold weather, homes have priority on natural gas deliveries. In extreme weather, gas-fired power plants sometimes cannot get enough gas to operate. Oil can make up the difference and keep the grid stable.

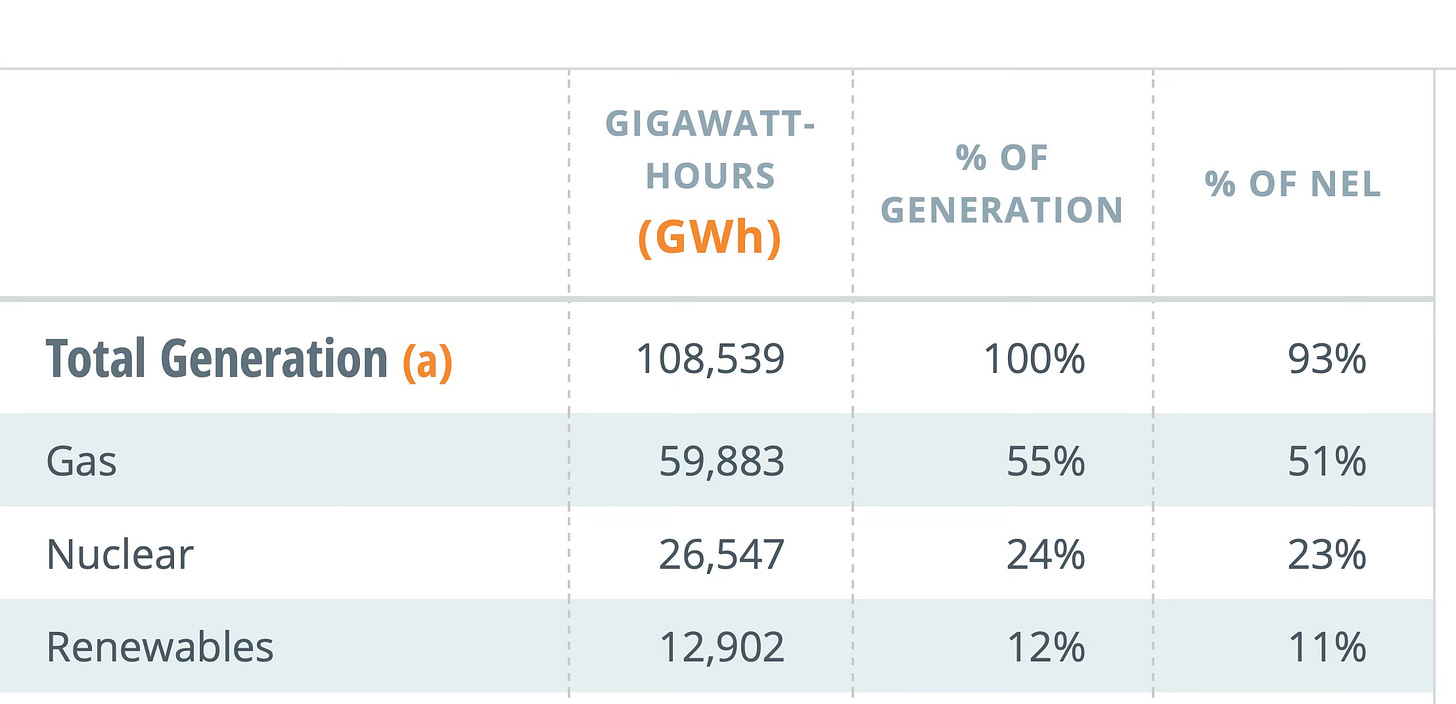

The New England is dependent on natural gas. Here’s part of a chart of fuel usage in 2024, from ISO-NE, our grid operator. It’s a large chart, so I cannot include the whole thing. However, near the bottom, the chart shows that oil was only 0.3% of overall fuel use on our grid.

Burning oil is only common in extreme weather. In contrast, natural gas was over 50% of our generation for all of 2024.

The Merits of Oil and Gas

Time to look at Merit Order for oil and gas. Oil is sometimes in Merit Order. But, what kind of oil is in Merit Order? Diesel? Distillate like heating oil? Bunker C?

I looked at the January cold snap, specifically for a high use day, around January 20.

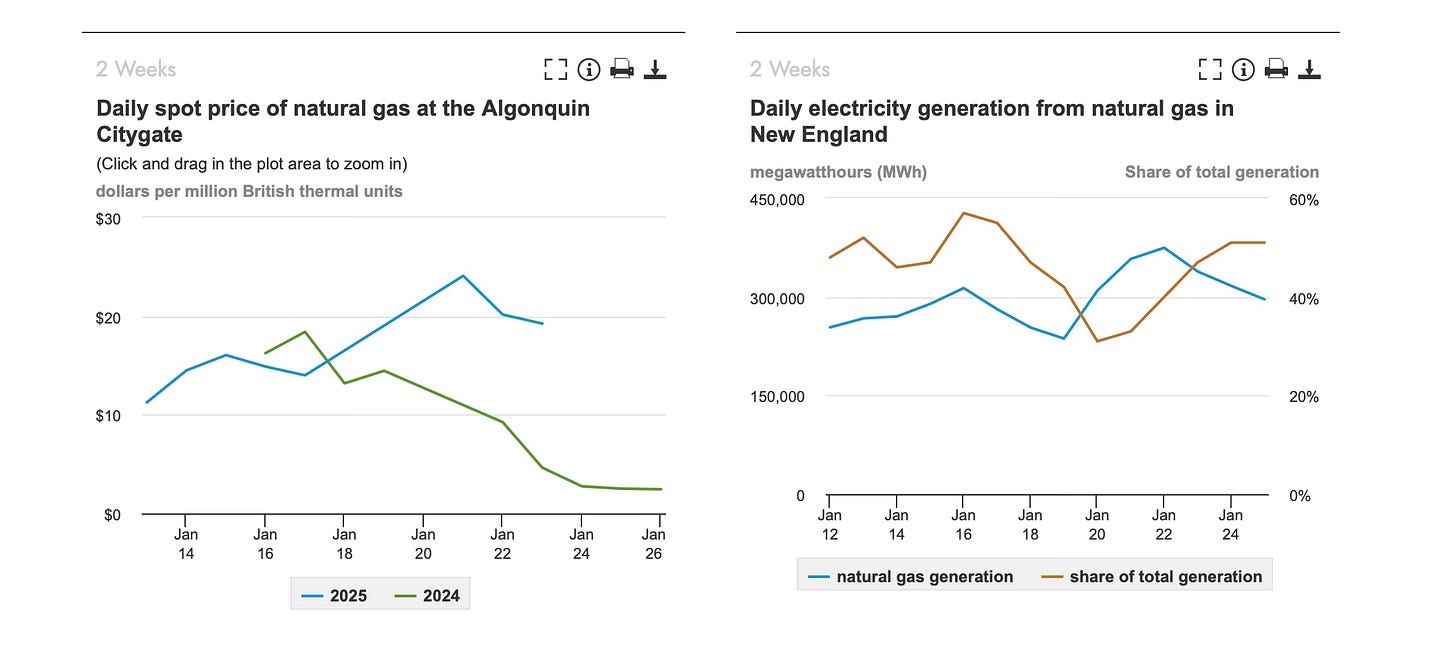

First, I went to the EIA dashboard for New England natural gas. (Screen shot below.) For my calculations, I used the price of $20 MMBTU for gas at Algonquin Citygate.

Around January 20, the percentage of natural gas on our system dropped below 40% as oil took over. This was a New England phenomenon. According to Ycharts for January 21, the Henry Hub (Louisiana) gas price was much lower at the same time.

Henry Hub Natural Gas Spot Price is at a current level of 4.40, down from 9.86 the previous market day and up from 2.35 one year ago.

What about Merit Order? Was oil actually cheaper than gas on January 21? I had to do some calculations because oil is usually measured per barrel while gas is measured as MMBTU. The calculations are below. 1

I looked at the price for 1 barrel of oil or equivalent amounts of natural gas. One barrel of oil would have been $75 if you bought West Texas oil at the Henry Hub, and the equivalent would cost $114 if you bought natural gas at Algonquin Citygate. So oil may have been in merit order for the power plants on January 21.

Most of the time, the price of natural gas is below $4 per MMBTU, even at Algonquin Citygate. This January cost situation was due to the cold snap.

However, I was not looking at the right comparison.

What is the right comparison?

I live in New England. Should I be comparing the cost per BTU of WTI oil at Henry Hub in Louisiana with the cost for natural gas at Algonquin Citygate in Massachusetts? No. We don’t have endless pipelines between Louisiana and New England.

This brings us to the important question: If a power plant in New England is burning oil….what is it burning? On the New England grid, the oil that is burned is a mixture of distillate and residual oil.

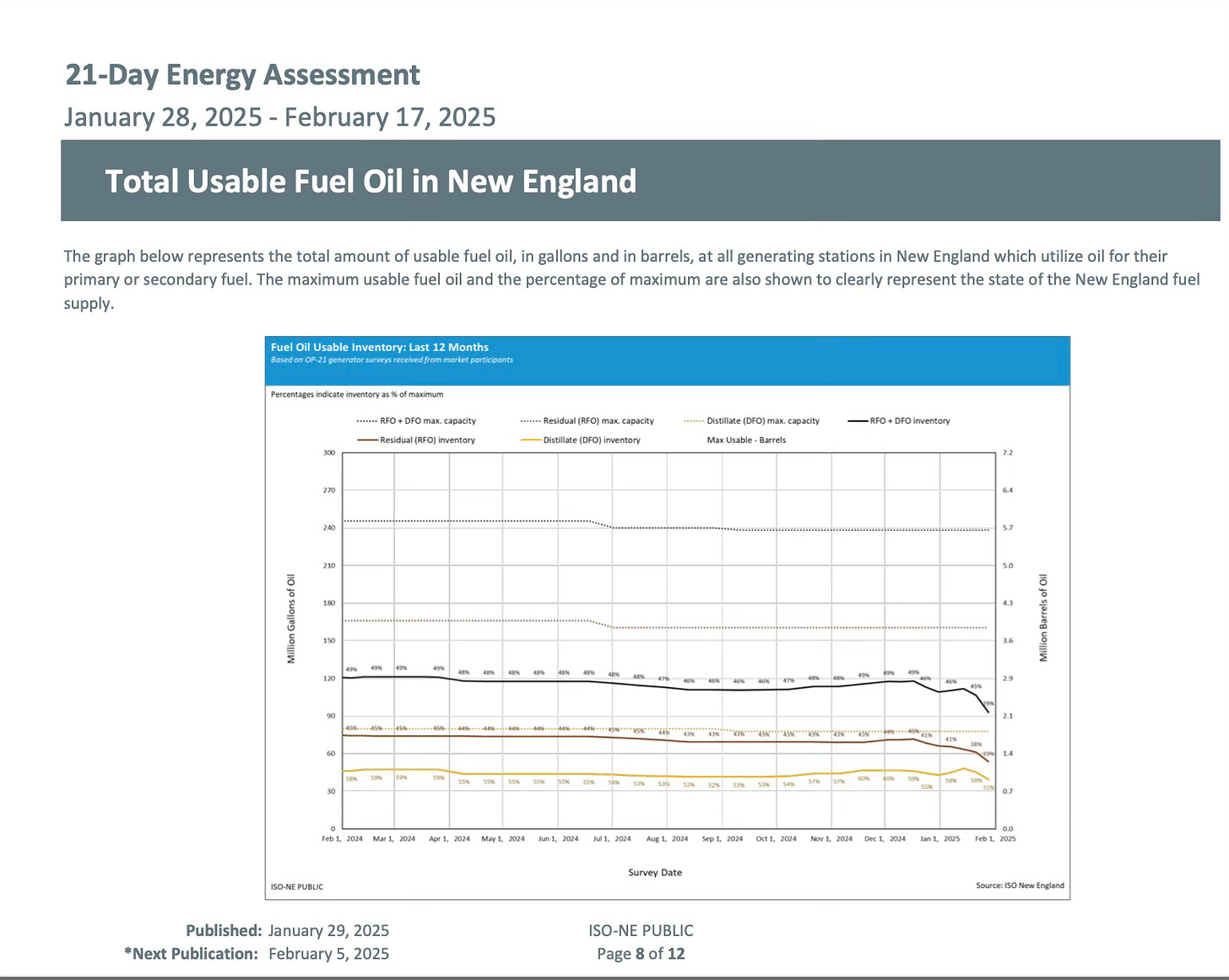

Happily, our grid operator publishes Operations Reports which distinguish between distillate and residual oil. The COO of ISO-NE, Vamsi Chadalavada, submits these reports to the NEPOOL Participants Committee. Here is the report published on January 28, 2025. The graph below is from page 8 of this report.

We can see that the oil inventory at power plants in New England contains about twice as much residual oil as heating oil. As the weather got colder in late January, the inventory of both types of oil fell. However, distillate oil has been partially replenished.2

What about the price of distillate? What about Merit Order? How is that going? There are so many types of distillate that it is hard to determine a single price. For this comparison, I will use the current price of heating oil, which has about the same energy density as diesel. At 138,000 BTU per gallon of heating oil, it would take 7.25 gallons of oil to provide the same energy as 1 MMBTU of natural gas. At $4/gallon of oil, it would cost $29 for 1 MMBTU of distillate oil. This is more expensive than $20 MMBTU for the equivalent amount of natural gas at Algonquin CityGate.

Therefore, as far as I can tell with my primitive calculations, on January 21, distillate would not have been in merit order, even when natural gas was $20 MMBTU. However, if you can’t get natural gas, then the next fuel in line is oil, at whatever cost.

Running out?

People ask if the Northeast is burning through its stored oil and will soon be in trouble to supply oil to the power plants. No. We are doing well.

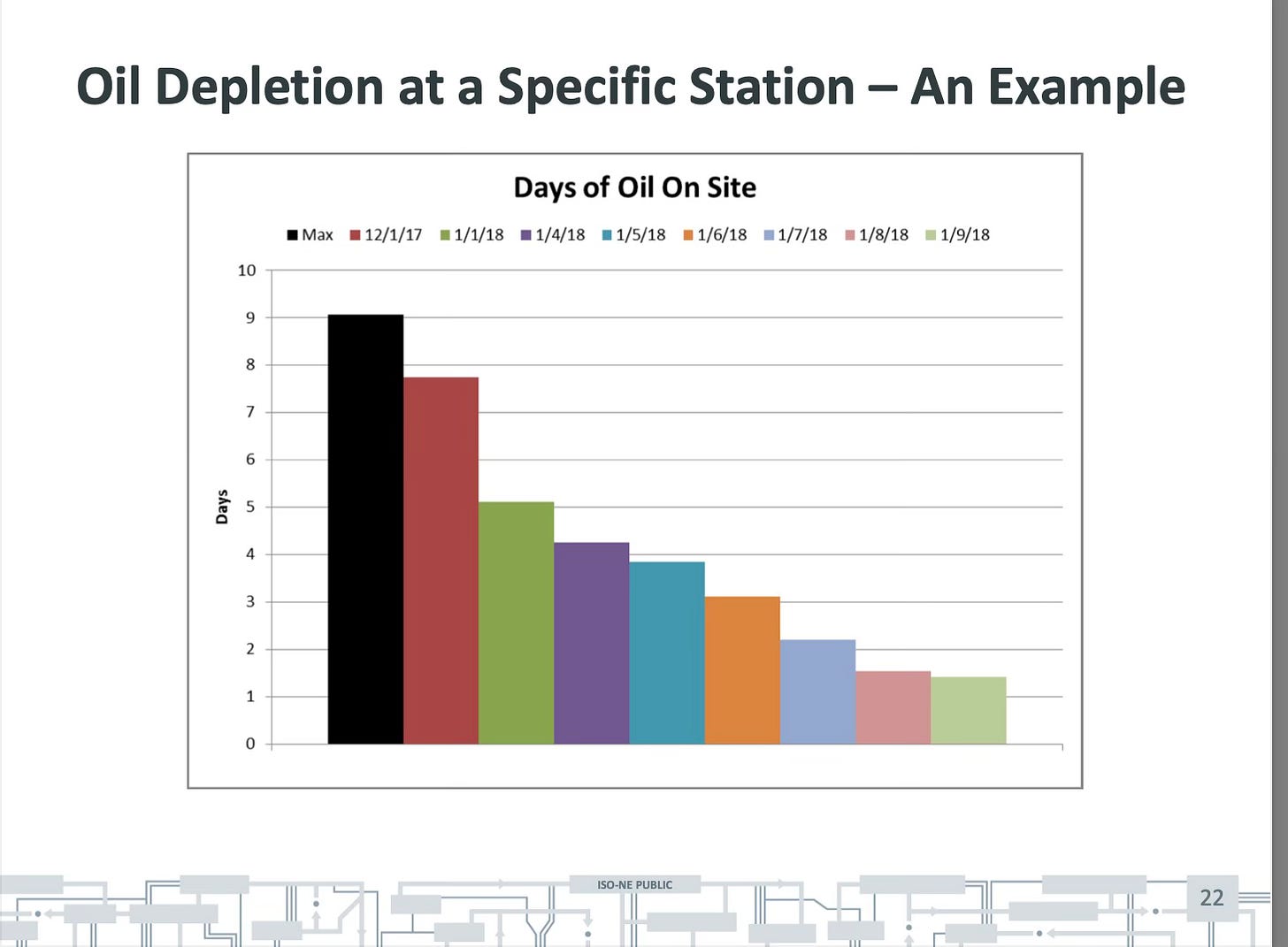

The situation is quite different from a few years ago. We had a major cold snap in 2018, and ISO-NE published a review of their response. I put a figure from that report (below) as Figure 5 in Shorting the Grid. It shows how close we came to running out of oil in 2018.

In contrast, looking at the Oil Inventory figure from 2024, we can see that the Northeast has a reasonable amount of fuel oil for the near future.

Peaks or Bases?

Oil is used on the ISO-NE grid when our pipeline-constrained natural gas system can’t supply peak demand.

Using oil is pretty primitive. Most Americans would be surprised that we have a large area of the country that depends on oil for 30% of its electricity. This sounds like a Caribbean island, not like New England. On the other hand, as I noted, oil-fired units (of all kinds), delivered only 0.3% of the electricity on our grid in 2024. When we need oil, we use a lot of oil. However, we don’t use oil very often. .

Several New England states have limitations on the amount of carbon dioxide that power plants are allowed to emit. These regulations limit the number of hours that coal and oil-burning plants can operate.

I think these regulations have some effect. However, when the weather is extremely cold and the grid is really stressed, the governors of the New England states often declare an emergency. This basically allows the power plants to burn whatever fuel they can obtain. I tend to see these carbon dioxide regulations as more greenwashing than realistic. We don’t burn very much coal or oil in New England. But when we need those fuels, the situation can usually be described as an emergency.

A boring grid?

I don’t look at this problem as “how do we meet or shave these peak usage days?” I look at it as “Why are we using so much natural gas?”

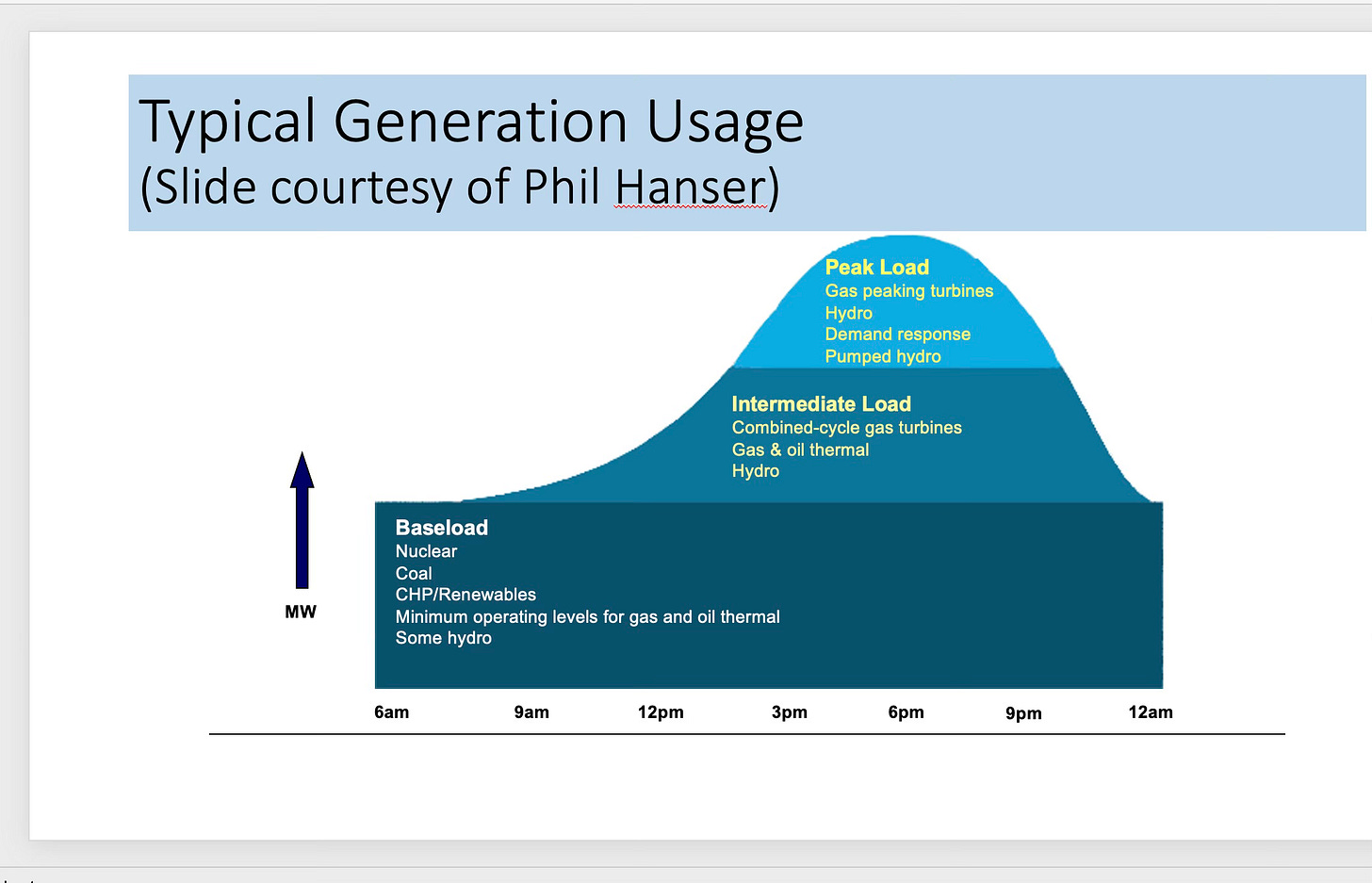

A slide below which I borrowed from Phil Hanser3 (with his permission) shows how natural gas permeates the grid. We use natural gas for combined cycle baseload, for intermediate load following, and for peaking. If we didn’t use natural gas for baseload and load following, we would probably have enough natural gas for peaking on cold days. With a solid base load of power plants with fuel onsite, preferably nuclear plants, the peaks wouldn’t require that much fuel.4

On the graph above, it is clear that the boundaries between different types of power plants are not fixed. Instead of looking at natural gas and thinking, “what can substitute for it sometimes?” we should be looking at the entire grid. We need to think about how to avoid being overly dependent on any one fuel. We need to have a solid baseload.

Meeting a peak can be dramatic! But I don’t want a dramatic grid. When we increase our base load strength, our grid will become more reliable and more boring.

Just like a grid should be.

WTI (West Texas) has been fairly steady around $75/barrel according to Oil Price. I am used $20 per MMBTU at Algonquin Citygate on January 21, and used the conversion factor that 1 barrel of oil is roughly 5.7 MMBTU. I came up with $20 times 5.7 for the cost of Algonquin Citygate gas with the same BTU content as one barrel of oil ($114)

Up-to-date information about oil or gas is a valuable commodity. You have to pay for it. One way to pay is to buy a subscription to Oil Price. I have not done this. I am only using information that is free on the web.

Phil Hanser and I were at EPRI (Electric Power Research Institute) during the same years. He is currently at Northeastern University. (Yeah, we have known each other for a long time.)

As I was writing this post, Hanser and I discussed the fact that renewables are not on his graph. As he noted, the graph is somewhat out of date.

My own opinion is that we could put solar on the graph as a peaking resource, but it’s hard to know where to put wind. Wind is not peaking and it’s not baseload. As Hanser said, different jurisdictions have different rules for how wind is treated. I look forward to many comments on this subject!

Oh, the what-if’s! What if Vermont Yankee had not closed? One can wish.

A combination of Net Zero, All-Electric Everything and a lot more "renewables" and storage would have made your "dramatic grid" far more dramatic and far more expensive. It might yet.